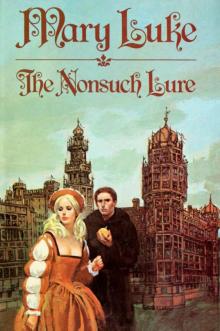

The Nonsuch Lure Read online

Page 6

Again, Rosa leaned toward him and spoke almost in a whisper. "Now, Mr. Moffatt, I'm sure it's a woman he's writing about. No young man would get that worked up over a palace, no matter how he longed to see it." She was silent, pondering the idea. "Yes, it had to be a woman. I wonder. . . . Sir, you're going to think me crazy, but I—I think—yes, I'm sure—I know the portrait he wrote about."

Andrew gazed at his Artless Charmer in amazement—and admiration. "But, Mrs. Caudle, how could you know?"

Rosa was already on her feet, impatiently brushing crumbs from her lap. "Oh, sir, do come!" She was excited. "Do come at once. I think I know the portrait he meant. And what's more"—she tugged at his arm, and again that deep pink edged her kindly features—"I think I know where it is."

Moments later Rosa was explaining to a patient husband that she

was going to show Mr. Moffatt the attic. Resignedly, Harry Caudle handed her a large key ring containing a dozen keys or more and waved her away. At the lift, Rosa instructed one of the waiters to bring Mr. Harry his tea at the desk. Then she and Andrew were on their way to the top of Cuddington House.

They emerged on the third floor. There were only three floors, Andrew knew from the building's facade. He was momentarily mystified when Rosa opened a door at the end of the hall and, in the dim light, he could see another flight of stairs. His companion was silent, puffing a little with her exertions, her flowered hat askew. "Now, sir, it's going to be a bit dusty and dark up there, but we always leave a torch or two right here on the steps." She handed one to Andrew, took one herself and closed the door behind them. In silence, they climbed the few steps to the attic.

It could hardly be called a room. Light from one window at the far end revealed a large expanse of vaulted space. Andrew could stand upright only in the center of the area running the length of the house. Rosa snapped on an electric light here and there, and with the aid of his flashlight he could see the handsome ceiling and thick oak beams with heavily carved bosses at each end. It was the original ceiling of the floor below. In the unfortunate "remodeling" of a hundred years before, some Cuddington had resolved on a way to get himself storage space, building the false ceiling for the floor below. This space might even, at one time, have been used as servants' quarters.

It was now, obviously, the repository for centuries of Cuddington castoffs. Trunks, suitcases, valises, eighteenth-century portmanteaus were cheek by jowl with an array of old Gladstone bags and an army rucksack, vintage 1916. The Cuddingtons had been a well-traveled lot. An old pith helmet lay in a basket filled with canteens and hip flasks; there was even a small cask that might once have held a good brandy atop a shabby Vuitton trunk. Above the luggage, mounted heads of antelope, tiger and gazelle gazed eternally into the gloom. Yellowing photographs of hunting parties, weekend shooting matches at country estates, peopled with buxom ladies and proper Victorian gentlemen, their guns held jauntily or displaying trophies, fined one wall. A broken chandelier, really a beauty, was spread out on a moth-eaten blanket on the floor, its pendants glimmering briefly as the flashlight's beam lingered on them.

One Cuddington had obviously been to India, for there were sev-

eral boxes of dulled Indian brassware piled against a broken folding screen of great delicacy. Overhead, hung against an oak beam, was a sword—broken and tarnished—the memento, perhaps, of a seventeenth-century Cuddington who'd cut a swath at the Stuart court? Or had it belonged to one of the gentlemen who visited the house when the rooms below had been used in the pursuit of illicit love?

On the other side were the larger pieces. Two lyre-shaped music tables, one with a lamp, its iridescent glass broken in several places, caught Andrew's attention. They were eighteenth-century—he'd seen their counterparts many times at Williamsburg. Two high-backed armchairs in faded and torn raspberry and mulberry velvet, trimmed with a silver almost black with age, looked even older. A doll's house in Palladian design caught his fancy. Pedimented and porticoed, it was a small gem—the birthday present of an indulgent father to a Cuddington child? There were dozens of walking sticks, some with yellowed ivory handles, propped in a broken umbrella stand of Oriental design. Nearby was an old hip bath. How many young maids had hurried up Cuddington House stairs with cans of hot water to fill that monster? A slate blackboard stood on an easel in one corner; neatly arranged on shelves were rows of books-children's books, devoted to the sea victories of Nelson and Wellington, gardening books, a history of King Arthur and several small velvet-bound volumes with clasps, probably locked and useless.

The whole space needed a good going over, Andrew thought. There must be dozens of valuable items in here, and the Caudles, so used to seeing them, doubtless didn't realize what a treasure trove they owned. Some weren't beyond repair; he'd seen many things in worse shape beautifully restored in the Williamsburg workshops.

"It's over here, sir. You'll have to help, I'm afraid." Rosa's voice came from behind the room's largest object, a large oaken armoire from which half a door was missing.

Andrew apologized profusely. Fascinated with the objects around him, he'd all but forgotten Rosa. She was tugging at something wrapped in heavy cloth, tied with a stout yellow piece of what appeared to be hemp. He helped her carry it from behind the screen, and together they brushed the dust from the covering.

"It's impossible to see up here, sir. Do you think we might take it downstairs where the light is better?"

Nodding, Andrew picked up one end. It was heavier than he thought; the frame must be pure oak. He wondered if it might not be too much for Rosa. "Just straight ahead and down the stairs-careful going down, sir." She didn't seem to mind the weight. "We'll take it right to our rooms, if you don't mind."

Once down the stairs, Rosa directed him around a corner. "Just at the end of the hall at the back, Mr. Moffatt," she said. Andrew was surprised at her agility. Rosa was a large woman, plump and nicely rounded. Yet she moved the portrait with a skill indicating many hours of arranging and rearranging hotel furniture. She rummaged in her purse for the keys, opened the door, and together they propped the picture against the wall.

The Caudles' quarters were cramped. Two rooms—obviously too small for guests, yet such as might have once been used by servants —were dark until Rosa switched on a lamp. She'd attempted to make them homelike and cheerful. Family photographs, vacation souvenirs and other mementos filled a table. The furniture was shabby—cast off from the guests' rooms, but not yet ready for the attic. Everything was neat and clean, with fresh scarves on bureau and table. An improbable dried flower arrangement and seashells stood on the mantel of a fireplace much too large and elaborate for the small room. This room and others on the floor had probably been partitioned off from what was once a large and spacious hall; the fireplace would then have been in proper proportion.

"We won't get much light in here, sir, but at least we'll have some privacy." Rosa had removed her hat, smoothed her hair and opened the desk, looking for scissors. Her face was flushed from her exertions and excitement.

"Mrs. Caudle, you're extremely kind to go to so much trouble." Andrew felt guilty. "If I'd known that frame was so heavy, we could have arranged for someone else to move it." He took the scissors and cut the hemp carefully. The cloth covering was linen or a heavy muslin, and the twine yellow with age. "How long has the portrait been up there?"

"Well, sir, I can't be sure, but at least twenty years. Oh, I do hope it's all right!" Rosa was obviously hopeful she hadn't led him on a wild-goose chase. "It used to hang over the fireplace here in this room. I always remember it being here when I was a little girl. It's very old, sir, and Harry and I thought it would be safer up in the attic. So we wrapped it up good and secure, as you can see. We

found the covering and hemp in an old box in the attic; I think they'd been used to cover this portrait before. Harry and I thought it a bit too fine for this room the way it is now. At one time, you see, all the rooms and the outside hall were really one large space— that's what i

t was like in the old days, sir."

A musty smell permeated the room as they carefully unwrapped the cloth from the frame. Andrew wondered if such protection had been necessary; any dampness in the cloth would only result in mold and ultimate deterioration of the picture. But the cloth was bone-dry, and, he remembered, so was the attic. This wasn't the kind of a house with a roof that leaked—it was probably as intact as the day it was built.

"The light is going to be poor to see this as it should be seen." Rosa was apologetic. Her voice shook slightly from excitement. "I remember it as very beautiful, and it will be nice to see it again. There we are, sir. Now stand back as far as you can."

Andrew could only go to the fireplace a few feet away, and he watched as the last of the covering dropped from the portrait. Rosa was right: the picture needed viewing from many more feet away, but this would have to do. She turned the frame slightly so he could look at it directly and everything came into focus.

The impact was tremendous. The room, Rosa Caudle, everything disappeared for Andrew the moment his eyes met those of a young girl, certainly no more than eighteen or nineteen, in medieval dress. She was an incredible beauty, and the artist had caught every nuance of her loveliness. Her hair was an extraordinary silver. Nearly white in its blondness, it seemed a halo for the strong, square face. Every feature had been lovingly fashioned and was alive with a vividness that almost leaped from the canvas. As a contrast with the pale skin and silver hair, the girl's eyes were deepset and gray with strong-winged, delicately arched black brows. Her chin was square with a deep cleft. It lent a sobriety to her expression belied by the gentle humor in her eyes—they were expressive and intelligent and framed in the darkest lashes Andrew had ever seen.

Andrew felt himself almost lifted from the room as though he were there in the picture with the girl. She was seated in a heavily carved gilt chair, her hands folded and relaxed in her lap. Her gown was simple, a delicate shade of peach, its square neckline trimmed with ermine, beautifully rendered so one could almost feel

its sleekness. A tiny cap of peach velvet, bordered with ornate scrollwork and pearls, covered a small portion of her fair hair; a golden circlet, from which a heavy diamond and pearl pendant hung, was clasped around her neck. The folds of her gown fell to the floor, almost covering the peach velvet sandals peeping from beneath its hem.

Andrew wrenched his eyes from the figure to study the background. It was remarkable. He was certain it was a Holbein, although he could recall no other work of that distinguished por-trayer of the Tudors that showed such perspective. The artist had seated his subject in the center of a room that seemed altogether familiar. It was sunlit, bright and spacious. At one end was a long mullioned window, and through that—a very unusual treatment—he could see a river and the corner end of an old stone building. The artist had reproduced a complete Tudor room—obviously the very one in which the young girl was sitting. A splendid Oriental rug on the floor was vividly patterned, each color superbly distinct and glowing in the sun's rays. At the far end was a handsome fireplace faced in what looked like Sienese marble, and over the mantel was a large portrait. That was innovative for the time, Andrew recognized—a portrait within a portrait.

He went closer to observe it. It was of an imposing square building, that also seemed familiar, of pale washed stone, its gleaming windows framed on the inside with opulent green velvet. There was even a suggestion of the interior sketched in. Large double doorways opened directly onto the street, and in front was a railing of strong wrought iron. A shield—or more likely a family crest—was set in the center. The small portrait was as detailed as the larger one of which it was a part. The perspective was striking, especially with the river scene outside; the collective impact of the portrait was electrifying.

"... it is nice to see it again and in such good condition." Andrew came out of his reverie to listen to Rosa Caudle. "And what do you think, sir?" I am speechless, Andrew wanted to say. He was astonished—and overwhelmed—by the radiant beauty of the subject. He cleared his throat as he helped Rosa lean the portrait against the wall so she, too, could observe it from a distance. "Who is it?" was all he could think to ask.

"Chloe Cuddington, sir. The granddaughter of the man who built this house. Her father was the one who owned all the land

King Henry took. She lived in this house for some time, sir, before she married Bartholomew Perm. He was a very famous artist. It's all in the history down in the lounge, sir. She was a famous beauty at court, too. She painted also, but never was as famous as her husband. He was a student of. . . of. . . ."

"Of Holbein," Andrew finished. Of course. That accounted for the pictures he'd seen at Sparrow Field. "B. Penn." They were Elizabethan and by a gifted artist every bit as talented as his master.

"That's it, sir. Here, I think there's something on the back. At least there used to be." She went to the portrait to turn it around. Andrew grasped one end, and together they read, in faded old-fashioned handwriting on what looked like parchment now almost brown with age, "Miss Chloe Cuddington. Painted by Bartholomew Penn, later her husband. At Cuddington House in the Strand. London, July, 1536 a.d."

"It was painted herel Of course." Andrew went back to look once more. "It was painted in what's now the lobby. There's the same fireplace." The Sienese marble had since disappeared, but the mantel was identical. He was very excited. It was tremendous to see what the ground floor of Cuddington House had looked like before it had been gouged out and scrambled to make a dining room, lounge, lobby and kitchens. "The whole first floor must have been one huge room," he said, "and that's what the view looked like when you could see the river." He pointed to the Thames through the window. "Very different now with the old Shell-Mex."

"And that's what Cuddington House itself looked like on the outside." Rosa pointed to the portrait within a portrait—the handsome pale structure with the coat of arms in its black railing. "A lot different today, more's the pity."

"More's the pity, indeed," Andrew replied, recognizing why the building seemed so familiar. More than once he'd tried to visualize it as it had been long ago, and now here it was, minutely detailed for him by a superb craftsman. "Mrs. Caudle, you've given me quite a treat!"

"And d'you think this is what Julian Cushing saw? Won't you sit down, sir? You do look a bit pale."

Andrew had completely forgotten about Julian Cushing. That girl has bewitched me, he thought. He sat in the chair Rosa indicated and lit a cigarette.

"I'm convinced that's what he saw, Mrs. Caudle," he said. "'A rare find of such beauty which set in me such a longing,'" he quoted from the Journal. "Yes, I'm sure that's what Julian saw. But one thing puzzles me. He mentions returning it to its owners. How did it get to Williamsburg in the first place? That's where he first saw it. He mentioned uncovering it with Miss Rosa Cudding-ton so she might see it when he arrived in London."

"Well, sir, I think it probably was taken by that James Cudding-ton to Williamsburg. Now let me see—if he was a James, he was a second son, and it had to be before 1700—right? So it could have been the great-grandson of the James Cuddington who owned this house, sir. He was the second son of the builder, and when the older boy, Richard, inherited the title and the Surrey lands, James got this house. Of course, later the king took all the land, so I guess the one who owned the house ended up better."

"And possibly," Andrew said, "when James Cuddington—who would have been quite an old man in 1699, when Julian first saw the picture—when he knew he'd probably never be going back to England, he was eager to have the portrait returned to the family. And Julian, having fallen in love with the girl in the picture, volunteered to bring it here. But that doesn't explain how the portrait came from Nonsuch as James Cuddington told Julian it had."

"That was probably James Cuddington's fancy, sir. After the Cuddington house was destroyed, the area around Sparwefeld became known as Nonsuch from the palace being there."

"Did the Penns have any children?" Andre

w had an inspiration. It was an odd thought and hardly made any sense. But then what had happened over the past twenty-four hours didn't make much sense either. "I mean they might have had a daughter who looked like her mother."

"Well, as to that, I'm sure I don't know." Rosa frowned. "I probably should know more about my own family, sir. But truth is, we've always been so busy here and at Sparrow Field. And we always did hear a little o' this and a lot o' that when we were youngsters, and it never seemed important to know any more." She seemed disappointed she couldn't reveal anything further. Then, brightening: "Sir, you might be interested in our family records. I don't know how good they are. But they're down in the safe—and some at Sparrow Field—and there are some up in the attic. We've quite a few letters and journals and things we never destroyed. It

seemed a pity to do so as long as we had the room to keep them. You're welcome to look at anything."

Andrew was touched. "Mrs. Caudle, you're very good, indeed, much too kind. You've given me great pleasure by showing me this portrait." Again his eyes met those of the beauty in the heavy gold frame, and he felt an unfamiliar tugging at his heart and mind. He tore his gaze away with an effort. Turning to Rosa, he grasped her hands. "My interest is even greater after seeing that magnificent picture. I would like to sift through anything you'll let me see. And now, perhaps, we should go back downstairs. I'm sure your husband is wondering what's happened to you."

He said good-bye to Rosa at his floor and went on toward his room. As he turned the key in the lock, it occurred to him that— once more—Julian's Journal had provided another coincidence: together he and Rosa Caudle had unwrapped a portrait, the same as Julian and Rosa Cuddington had done more than two hundred fifty years ago. It was, without any doubt, the same picture. And he had reacted the same: he'd fallen in love with Chloe Cuddington just as Julian had. "And I hope I withheld my passion from her gaze." He smiled at himself as he closed the door.

The Nonsuch Lure

The Nonsuch Lure