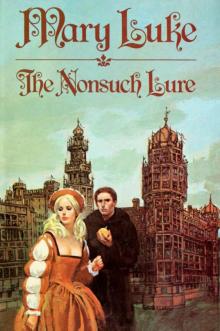

The Nonsuch Lure Read online

Page 3

Cuddington House was the birthplace of Sir James' son, Richard, who was to become the well-known Tudor artist. It was also the residence for a time of Bartholomew Perm, a student of Hans Holbein, who immortalised the Tudor monarchs and many of their court. Penn was the husband of Chloe Cuddington, a granddaughter of the builder. She and her young husband were great favorites at the court of Elizabeth I.

Cuddington House was a private residence until 1842. It survived the Great Fire and the attempts of later owners to sell it for a more fashionable residence, a difficulty which increased with the years as the Strand became a more commercial thoroughfare. In 1730 a mistress of George II was lodged in Cuddington House while heirs of the late baronet fought over its disposition. The royal mistress brought several of her friends to the house, and when the court case was settled, the owners decided to make it an inn. It was run on an informal basis, mostly for the convenience of court ladies and gentlemen [a nice touch that, thought Andrew] for several years, and when Queen Victoria came to the throne, the owner, a spinster lady, Miss Chloe Cuddington, remodelled the building to take in paying guests from the public.

In 1933, the premises were thoroughly modernised, and it is, substantially, the building the visitor sees today."

Well, by God, a royal bordello. That's an unexpected bit, he thought, and they hadn't balked at including it either! And since Rosa Caudle had said she was a Cuddington, there was even a baronet in the old girl's ancestry. 1520 and on. Henry VIII and the Field of Cloth of Gold. Cardinal Wolsey and Sir Thomas More.

Mary, Edward and Elizabeth Tudor and that passel of six queens who had died, were divorced or beheaded, who had spent their married lives—some of them very brief, he remembered—trying to give their husband an heir to the Tudor throne. All had seen this house in its prime, as had Raleigh, Essex and the first Stuart king. Even William Shakespeare must have passed it often. Had they all regarded it as unique for their time as the plaque implied?

The paragraph that interested him most—so much so he read it twice—was the one noting that it was the Cuddington family who'd owned the vast lands King Henry had confiscated so he might build Nonsuch. What arrogance! To annex a whole village, wipe out a church, a priory and a manor house so a residence might be built to make hunting more convenient. Was that the reason Henry had taken Cuddington? The plaque made no mention of the cause; he looked again to be sure. Yet that must be the explanation—it was odd he should think of a motive when one wasn't even noted.

He also reread the paragraph referring to James Cuddington. Julian had mentioned a gentleman of that name in Williamsburg. It had been a James Cuddington who'd provided that holiday "merriment" Julian had shared. It must have been one of Rosa Caudle's ancestors—a descendant of the man who'd built this very house— who had emigrated to Williamsburg a hundred or so years after Henry had built his palace.

It was all very confusing and exciting, and Andrew mulled it over a few moments later while enjoying what he privately considered one of the world's vanishing wonders: a traditional English breakfast. Strawberries and cream, eggs and fried mushrooms, a plate of hot muffins—and cold toast in the British manner. Small vats of sweet butter and a choice of several preserves, marmalades, jams and jellies were already on the table. And everything was accompanied by several cups of steaming China tea, brewed to the turn.

Andrew glanced around the room, wondering if it had been used for dining when Julian Cushing was visiting. Probably not—Julian would have eaten in the Great Hall outside with the family or gone to a nearby pub or inn for his breakfast of ale, meat and bread. "Victuals" he'd have called them. Odd the name should pop into his head. The room that now served as the dining room faced away from the busy Strand and would, in Julian's day, undoubtedly have looked out on a garden or courtyard bright with sunshine.

Now it was hedged in and windowless. At its back there was probably a dank alleyway where trash was collected, with an entrance for the help.

Finishing his tea, he reflected on the coincidences of Julian and himself both coming to England because of a ruined palace—of both staying in the same lodgings and being taken care of by women who'd borne the same name and served in the same role. He wondered what Mrs. Caudle would think if he were to tell her the story.

She was waiting at the desk, train schedule in hand. Transportation ran very frequently, she said. Andrew realized they were probably commuter trains, bringing workers to London in the morning and spewing them out at night. He really would have preferred a car, but his hostess was explaining about the train. She seemed unusually pink and breathless. She leaned toward him and said, "Sir, please don't think me forward. I asked Harry, and he said it would be all right, you being a gentleman and all." She stopped, a bit unclear as to just what to say to this nice good-looking young man.

There was a long moment's silence as she grew pinker before Andrew, relishing a confusion he found endearing, rescued her, "Tell me what, Mrs. Caudle?"

"About Sparrow Field Farm, sir. It's our place. Where Harry and me will retire one day. It's at Nonsuch—well, not exactly, but very nearby." Again confusion reigned, and she gripped the counter determinedly, ready to give it another try. "It's a house a little way from where Nonsuch Palace used to be, sir."

"You have a house there?"

Andrew's question brought forth one of Rosa Caudle's broadest smiles. "It's a house quite near where the palace used to be. We stay there whenever we can get away. We went there last week to see the excavating and things."

"And it belongs to you and your husband?" This was getting better every moment. Fancy old Harry and Rosa having a house near Nonsuch Park!

"Oh, sir, it's been in the family forever! It's older than Nonsuch!" She smiled again, more relaxed. And then, fearful she might have sounded too grand: "Of course, it's not a big place, sir. Not nearly as large as it once was. And there's not nearly the land around that used to belong to the house. But Sparrow Field is still there, and a

farmer watches over it for us when we're up here. He gets the produce from the kitchen garden and his lodging for his wages—what we don't use here, that is." And she gestured vaguely in the direction of the dining room.

Andrew now understood the wondrous simplicity of his breakfast —all from a country garden only twenty minutes away by train. All served in a Tudor showplace, much changed, but still maintained and obviously cherished by the same family. And all because he'd picked up a fifty-dollar Journal and a travel brochure. Rosa interrupted his reverie. "And so I asked Harry if it would be proper for me to tell you if you went to Nonsuch by train—and you'd pass Sparrow Field on the way, sir—if, after you've seen the ruins—and they can be pretty dusty and tiring—well, you may want a washup and a pot o' tea, and you can get them at Sparrow Field. And that's what I asked Harry!" She finished triumphantly in a flurry and blushed another shade of pink.

Andrew thought maybe he'd fallen in love. Julian had called his Rosa Cuddington a "very Perceptive Woman." Andrew now labeled his "the Artless Charmer." He would indeed look in at Sparrow Field, he said and, thanking her and bidding her good-bye, walked on through the lobby. Sparrow Field. The name seemed familiar. Then he remembered. In his Journal, Julian had written that Miss Cuddington had arranged for him to stay at Sparwefeld Farm in the park near Nonsuch which the Cuddington family owned. Could Sparwefeld and Sparrow Field be one and the same? If so, it was yet one more link in what was fast becoming a remarkable chain of similarities. Then the clock on the stairway landing chimed the hour, and he hurried on. He didn't want to miss his train.

Sitting in the comfortable first-class carriage, Andrew rummaged in his briefcase for some Xeroxed sheets Miss Dabney had made for him. They were brief extracts from the writings of the British antiquarian William Camden and were valuable for the description of Nonsuch Palace as it appeared some forty years after its completion. In delightful Tudor English and spelling, Andrew read:

"About four miles from the Tamis within the Country, None

such, a retiring place of the Princes putteth downe, and surpass-eth all other houses round about; which the most magnificent

Prince, King Henrie, the Eighth, in a very healthful place called Cuddington before, selected for his owne delight and ease, and built with so very great sumpteousnesse and rare workmanship, that it aspireth to the very top of ostentation for show; so as a man may thinke, that all the skill of Architecture is in this one peece of works bestowed, and heaped up together. So many statues and lively images there are in every place, so many wonders of absolute workmanship, and workes seeming to contend with Romane antiquities, that most worthily it may have, and maintaine still this name it hath of Nonsuch. . . ."

Camden was like the many others who'd seen the palace in its prime. All had praised its exquisite beauty in elaborate phraseology that, even allowing for the ostentatious mode of expression fashionable at the time, left little doubt the king had succeeded in erecting a peerless structure. Its fame had spread throughout Europe. Nonsuch became so celebrated that the first place a foreign ambassador invariably wished to see on arriving in England was not the venerable Abbey or the Tower—but glorious Nonsuch Palace.

At Ewell, a half hour later, Andrew asked directions for Nonsuch Park and, walking the pleasant streets of the little Surrey village, attempted to envision how it might have looked in the sixteenth century. Buildings still in existence could have witnessed the passage of the king and his party returning from a morning hunt. He could picture old Henry coming upon the little village of Cuddington, surrounded by forests full of wildlife, and deciding to appropriate the lot. A priory, a manor house, a church and a village. Andrew wondered how he himself would have felt if he'd owned it all—several thousand acres and a half dozen buildings—and had it all wrested from him. It was a fruitless attempt at guessing—everything was too far removed from one's own experiences. And over the centuries there'd been a great change in values. In those days, he remembered, the monarch was much venerated. Richard Cuddington might have been honored at the king's action. . . .

So preoccupied was he that he didn't realize he'd left the village behind. Suddenly he was walking on an unpaved road with thick hedgerows on either side. Large stones, moss-covered and deeply embedded in the earth, lay beneath giant sycamores, their boughs dipping and bowing in the midmorning breeze, creating an ever-

changing pattern of sunlight in his path. The stillness was broken only by the cawing of birds.

To his left, a team of dun-colored oxen, led by a man in heavy stained work clothes, tediously plodded through the field. The birds were diving into the furrowed earth, picking up seeds, worms and larvae. Up ahead, the sound wafted from a large tree where other birds had taken possession, chattering and talking to each other, darting from the branches to the ground below. Andrew had never seen so many birds at one time. He stopped to watch. The bottom of the tree was hidden by a red-brick wall that followed the line of the road. The birds were diving from the tree to something inside the wall, then triumphantly returning to the green lushness of the boughs.

Arriving at the gate, he looked into the enclosed courtyard to see what was proving such an attraction. A grizzled old man sat on a bench under the tree, out of the sunlight that streamed on the path leading from the street. The path followed in a beautiful circle, ending at the front door of a substantial farmhouse at the far end of the courtyard. Clumps of rhododendrons, day lilies and fuchsias softened the outline of the building that looked remarkably fresh in an area where most had taken on the soft patina of age. To one side of the house a corner of a garden was just barely visible, an oasis of green planting, interspersed with rose bushes, phlox and hydrangeas enclosed by a wall magnificent with honeysuckle and wisteria. An old spaniel padded from behind the house to the shade of the garden's largest tree, an imposing beech, and settled himself at its base. He disdained to watch the old man, who sat with a large cloth bag in his hand and, muttering and calling, was throwing seed out to the birds. Some came close to him; others, more daring, lit briefly on his shoulder or atop his greasy cap until he impatiently brushed them away, muttering even louder.

It was a charming scene, reminding Andrew of those hordes of kindly citizens he'd watched in many of the world's parks as they gathered daily to feed the birds and squirrels. The man sat squarely on the bench, his feet shod in leather sandals. He wore a short faded coat and pants of some rough material; they seemed banded or tied at the knee. Andrew could not make out his features, as his cap was pulled down on his head. The man's voice was crooning and soft, and he flung the seed with an agility belying his age. He fitted perfectly into his surroundings, blending with the solid sub-

stance of the farmhouse in the background. Rather grand for a farmhouse, Andrew thought, as he reluctantly left the scene, reflecting what a perfect painting it would make.

At the end of the unpaved road he joined the main thoroughfare. There were the signs: nonsuch excavations—straight ahead. The area seemed busier and more alive than back at the farmhouse. Trucks and automobiles sped by, filled with what he assumed were site workers. Few were sightseers. Undoubtedly, the weekend would have been prime time for visitors, and he hoped this early on a Monday morning he'd be able to observe the work without the distracting presence of too many tourists.

He followed in the wake of the trucks, entering the park through a wrought-iron gate. It seemed familiar, and when he saw the long treelined drive just ahead, Andrew realized this must be the very gate he and that serving girl had passed through almost a quarter of a century before. In every direction he could see, there was no other line of trees ending in a gate.

There were a few workers in the trenches, and as he stood above them, everything professional in Andrew reacted to what he saw. There it was—spread out before him—the excavations of a royal dwelling from Tudor times. A palace that had so intrigued him as a child its spell had lain dormant for nearly twenty-five years. Even the tents, the huts for equipment and portable vans at one far end of the field, could not detract from the joy of the moment. He'd been right to come.

Looking off to the distance, he found Nonsuch Park even more impressive than he remembered. To the south the land fell away in a gentle slope. Off to the east were dark clumps of beech, oak and elm—the remains of the vast forest that had once covered the whole site. Nonsuch lay at the foot of the North Downs, and in Tudor times much of the land would have been arable with the forest providing protection and cover for pheasant, partridge, foxes, hare and deer. It was still clear and kept open for public use with no dwelling except an old farmhouse to the west. Many of the trees, especially the Spanish chestnut and oak, grew to great heights; they were very old. And for the rest, there was that smooth, incredibly green grass where he'd run and flown his kite. It did not seem very long ago.

From where he stood, the excavations appeared to be near, even possibly on, the very site where he and the girl had picnicked.

They'd spread the contents of their basket under the trees on one side of the roadway leading to the gate. From what he could see before him, it appeared that all the while they'd been sitting atop the palace foundations.

Andrew walked toward the eastern rim and, with a professional eye, noted the size and condition of the foundations on which Nonsuch had stood. It had not been as large as Windsor, Greenwich or Richmond or even—by Tudor standards—as large as the homes of several of Henry VIII's more prominent nobles. It had never been intended as a lodging place for the whole court Instead, it was to be a royal residence—an extravagant one, to be sure—where the king and a few of his companions might seek respite from the affairs of court or hospitality after a long and vigorous hunt. Henry Tudor had had great fondness for Nonsuch and had spared no effort or expense in its ornamentation. Stone from Liege and Caen, Andrew remembered reading from Miss Dabney's notes. Lumber from forests for miles around. Real glass in the windows. The renowned Nicholas Bellin of Modena, a veteran of many of the French king's fancies including the glorious Fontai

nebleau, headed scores of workers and craftsmen.

The trenches were rapidly filling up. Several workers, obviously student volunteers, were filling wheelbarrows with rubble, decayed roots, broken stone, brick and earth. Farther off, near the southern end, a bulldozer approached a section where other workers waited with barrows and carts to remove the displaced earth.

The sun was beginning to climb higher. Andrew took off his coat and slowly walked along the perimeter. At the remains of the kitchen buildings, he saw small deposits of animal and poultry bones, oyster shells, charcoal and fragments of kitchen utensils lying beside piles of cobbles from the courtyard. A well of surprisingly fresh-looking Caen stone had yielded pieces of rubble—balus-trading from the palace and chunks of decoratively carved blocks— that lay piled near other fragments of pottery, pewter and glass.

Adjoining the kitchen block was a cleanly excavated area. Old Henry's wine cellar, a workman told him. When Andrew commented on its size—more than sixty feet in length and eighteen feet at its widest, with walls six feet high—the man told him that over a hundred tons of rubble, including broken bottles and flasks, had been removed before the walls became visible. Stone steps led to

the cobbled floor; they interested Andrew so much he asked permission to look at them closer.

He took a small magnifying glass from his briefcase and minutely examined the large blocks of stone that appeared different from the others. No doubt they'd come from some other structure; some contained carvings, some were smooth, some were rough. One even had a Norman roundel, as perfect as the day the carver had laid aside his tools. Some building had obviously been destroyed, and the king's workmen had saved time and expense in using the blocks for constructing the wine cellar. The square joist holes in the walls where the wine racks had stood were clearly evident, and three stone-lined drainage gullies ran down the sides and middle of the cobbled floor to meet in a soakaway in the center. Water had been piped into the cellar for washing vessels and casks—a skillful setup for the early sixteenth century, Andrew thought.

The Nonsuch Lure

The Nonsuch Lure